The term ”social learning” is not something that appeared when we formalized education systems or implemented technology in L&D departments. As humans, we have always passed knowledge and culture in narratives. To this day, stories and tales allow us to observe, imitate and model other people’s behaviors. In other words, we learn (and we have always been learning) socially.

Which is why, structured social learning as we know it cannot be separate from the workplace experience. It is common for companies to treat learning and development as a ‘thing of its own’. But, what if instead, we started treating it as part of the social experience at work? What if we focused on getting people to share more of what they already do at work (learn, think and discuss) while in the learning process?

In the end, it’s all about telling more stories! It’s about creating a dynamic learning environment that sparks excitement, replication, and engagement. Keep on reading to learn how to leverage structured social learning and get your team to become active participants of their skill development.

Wait…what? Let’s start from this: we are all enchanted by stories. Stories offer us a complete world of wisdom and explicit experiences so we can learn from those around us. Every person we meet carries a story of their own; with its own set of experiences and perspectives.

That’s why, no matter the setting, we can always acquire new behaviors and knowledge by watching others. Learning nerds tend to call this process “vicarious learning”. This is when people learn through indirect sources, such as hearing or seeing something happen, empathizing with another’s story or dealing with a challenge.

Vicarious learning is rightfully stimulated if the social environment creates two things. Firstly, it increases the chances of replicating behavior (aka, it helps someone observe others taking an action, understand the reason behind their success or failure, and visualize themselves taking the correct course of action). Secondly, it reinforces the behaviors that led to learning (aka, it helps people model and change their behavior through people they trust and share a purpose with).

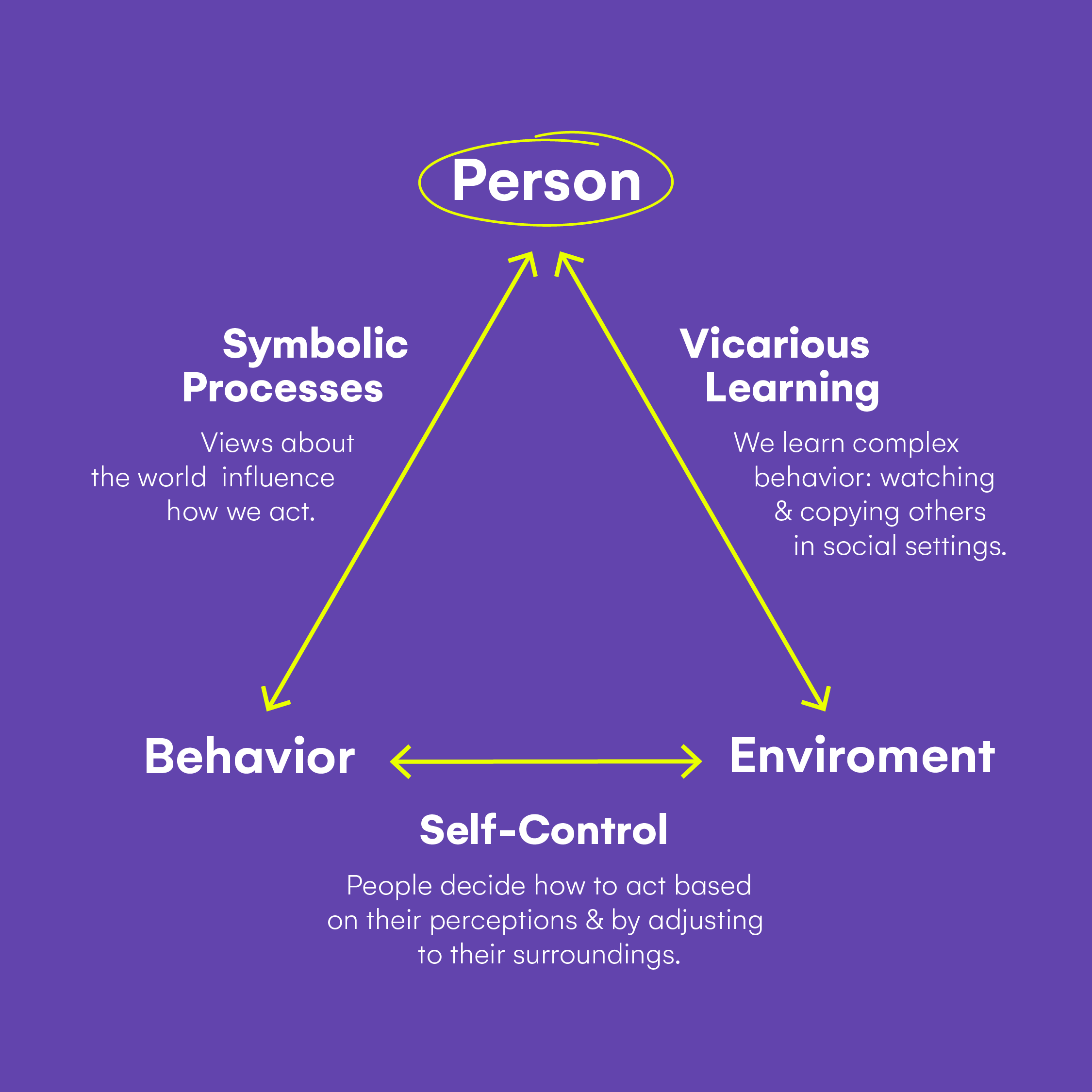

These simple thoughts, prompted Psychologist Albert Bandura to study what we today refer to as “social learning theory”. This theory integrates both behavioral and cognitive theories of learning in order to provide a comprehensive model that may account for the bigger range of learning experiences that happen in day-to-day life.

So, do we as human beings simply observe and copy? Do our learners simply observe a training program and imitate rightfully? Is that all vicarious learning and social learning? If that were the case, learning professionals would have had their work easily cut for them when creating any learning intervention.

We call them stories, but there’s much more to it. There are mental factors mediated in the learning process that determine whether a new response is acquired. Individuals do not automatically observe the behavior of a model and then imitate it. There are some thoughts prior to imitation.

This occurs between observing the behavior (stimulus) and deciding whether to imitate it or not (response). This is called the mediational process.

Social environments amplify these mediational processes. However, their effectiveness relies on how the learning experience and social elements of it are structured. As per Bandura’s insights, there are five key principles that determine the effectiveness of these social learning environments: attention, retention, similarity, motor reproduction, and motivation.

So, as we said before, social learning theory means creating a good story. But how does learning and stories work together?

How can you assess whether your training experiences have the right elements to create an effective social learning experience? It starts with accepting that it’s part of the workplace experience. When thinking of Bandura’s principles, try to step into the learners’ shoes and ask yourself the following five questions:

1- Attention: Is this lesson worthy of my time?

Without attention, a learner fails to form a mental representation of the behavior the experience aims to teach. For a behavior to be imitated, it has to be stimulating. It has to be rewarding (through feedback or recognition) enough for us to believe there is a benefit from it and relatable (knowledge-wise & culture-wise) enough for us to believe that it’s feasible for us to approach.

In practice, it’s the difference between someone remembering a presentation and zoning out. When the presenter reads off the slide, uses a monotone voice and lectures, people disconnect from the story they’re sharing. When they’re left with a feeling of relatability and involvement, they’re more likely to actively listen.

Case studies help learners tackle and practice analytical skills. To make sure they succeed, case studies must be relatable to the learners’ daily experience. This will help remove any frictions and make sure they’re provoked enough to take action.

2- Retention: Is the content engaging enough to retain this information?

Retention is about how well knowledge, skills and behavior are remembered. Behaviors may be noticed, but they don’t always stick, which prevents imitation and repetition.

Learning experiences must have reinforcement mechanisms or follow up activities if we want the behavior to be performed later by the observer. This is because much of social learning is not immediate, so this process is especially vital. Even if the behavior is reproduced shortly after seeing it, there needs to be a memory to refer to.

For example, follow up retention by organizing a live discussion on a shared resource to get learners talking about a piece they’ve already read. Talking about it – after reading about it – with others will repeat the content in their memory and improve retention through socializing.

This is called “peer reviewing”, where learners work in small groups to review content previously presented. It will get people to check for understanding of a topic while helping them retain the information better through collaboration. Instructors adopt the ‘facilitator role’.

3. Similarity: Do I trust who is speaking?

We are more likely to model the behaviors after individuals who are similar to us. Ultimately, this comes down to trust. To achieve this, learning experiences should include ways for the person with the knowledge (instructors) and receiver (learners) to build proximity and similarity.

Proximity refers to how close learners feel to their instructors – how easy it is for them to reach for help or get feedback, for example. As for similarity, it is the idea that if we are learning and doing new things with people who are similar to us, such as our team colleagues, we are more likely to engage in the process.

This can be done through discussion forums, boards, chatting tools or software with embedded chatting features, creating posts with open ended questions to create conversations and lots more. Communities can be built synchronously and asynchronously; all you need is to allow a channel for it to happen.

4. Motor reproduction: Is the notion explained well enough that I can replicate it?

Learning experiences are all about application, actions and practicality. If that aspect fails then we merely witness an awareness session. This influences our decisions on whether to try and imitate it or not.

Many learners can consider the intellectuality and functionality of a theory or process. But it’s only once they apply it that they can appreciate its benefits. It’s at this point that they can decide how rewarding it may be if they decide to master it.

When learners are assigned roles of importance during your experience, they can help others and hold the structure of your learning plan. Roles can be: coordinator for assignments, group leader, discussion mediator, activity coordinator, etc.

5. Motivation: Am I motivated to take action?

Possibly the toughest to measure, but easiest to observe. A learner will take action if the perceived reward of doing so outweighs the perceived cost. If reinforcing the behaviors is not important enough to the learners, they will not imitate it.

What’s important to remember is that this decision is subjective to the learner’s goals, how they like to be addressed, communicate, and learn. So, to motivate learners to take action, you have to think about what moves them towards action. In other words, what goals do they have and what do they consider a reward?

We’ve looked at the role of purpose and relevance, but what drives motivation is having agency. To create a sense of agency among your learners, create multiple objectives for the learning experience. This way, they’ll have multiple options to work towards.

And yes! That’s exactly what Stephen Covey’s 5th habit says, and it can work tremendously well here. Seek to understand what behaviors are seen as worthwhile by your learners. Whether that’s praise, recognition, positive feedback, merits or even points in a gamified learning system.

Once you have identified those core behaviors, place your learners in a situation that rewards multiple behaviors and make them understand the value of imitating or reproducing them (aka, the reward).

So, as we wrap things up, remember this: “social learning” isn’t a newfangled idea. It’s been in our DNA long before formal education and tech-driven L&D departments. What makes social learning work is stories. And we’ve always shared knowledge and culture through narratives and stories – they let us observe, imitate, and model behaviors.

In other words, creating a good story – a story that encourages the imitation of certain behaviors and the replication of them – is at the heart of learning because it results in vicarious reinforcement (and as such, vicarious learning). To make it work, we’ve got to grab people’s attention, make the content memorable, build trust, ensure practicality, and keep them motivated. If you can create training experiences that prioritize a few or all of those things, you’ve found the secret sauce of social learning.

Reviews